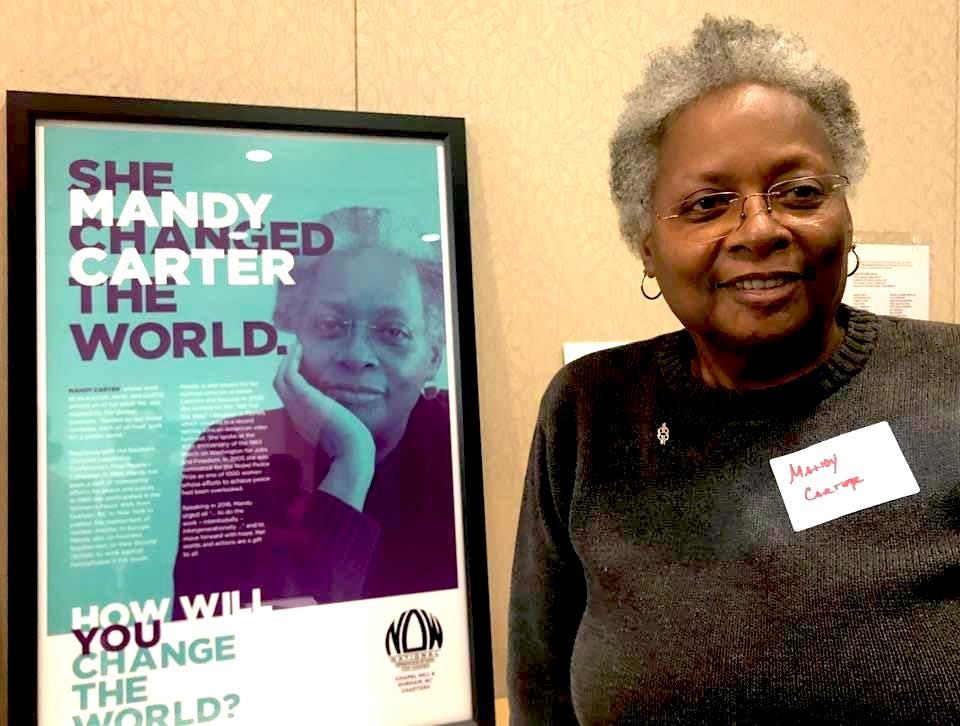

Dear Friends, as we nagivate the daily assaults of the current administration, this month’s profile of Mandy Carter is a reminder of the difference each of us can make. Even the smallest things can ripple out to have tremendous impact. Truly, in this interdependent world, there is no such thing as an insignificant act.

I have known Mandy Carter for more than 40 years. She is a lifelong activist and organizer. Since 1968 she’s been serving the cause of peace and social, racial, economic, and LGBTQ+ justice. Mandy keeps her sleeves rolled up and her boots on, ready to engage.

When I was searching the internet for photos to include with this profile, there was Mandy, standing with Coretta Scott King, on panels with Julian Bond, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez, and Daniel Ellsberg. Speaking on CSPAN and at rallies on the National Mall. Leading a 600-mile Women’s Walk for Peace to protest the army’s shipment of missiles to Europe. Producing concerts and cultural events that fundraised for movement causes and brought people together. There were also countless smiling photographs of her with groups of people—mostly young people— doing the frontline work of creating a more just and compassionate world.

Mandy is a co-founder of the organizations Southerners on New Ground (SONG), and the National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC). She led the historic North Carolina Senate Vote ‘90 campaign that sought to unseat archconservative Jesse Helms and elect Harvey Gantt, the first African American Mayor of Charlotte, to the US Senate. Although they did not prevail, as Mandy says they “failed forward,” laying the foundation for solid LGBTQ multi-issue alliance-based organizing in the state.

Now in her mid-70s, Mandy still drives back and forth across the country, speaking at conferences and universities, consulting with local movements, and doing voter mobilization. She is a member of the National Council of Elders, founded in 2011 by Vincent Harding, James Lawson, Phil Lawson, Dolores Huerta, and Grace Lee Boggs. The Council brings together 20th-century movement leaders with young leaders of the 21st century, to promote the theory and practice of nonviolence. They seek to foster “a radical revolution in values against racism, materialism, and militarism while bringing to life beloved communities.”

Mandy was raised in two orphanages and a foster home in upstate New York. In 1965, during her junior year of high school, her social studies teacher brought in a guest speaker from the Quaker-based American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), to talk about peace activism and the ongoing struggle for civil rights. At the end of the presentation, the speaker told them about a week-long AFSC summer work camp for high school students to learn the philosophy of nonviolence, direct action, and social change. Mandy immediately signed up.

“That one 40-minute class changed my life,” she says. “It planted a seed. If I had not gone to that camp, I never would have heard the name Bayard Rustin or learned about the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence.” Rustin, one of the key architects of the 1963 March on Washington, was a Black gay Quaker activist and organizer who worked with Dr. King during the Southern Freedom Movement. He became a central inspiration to Mandy, and remains so to this day.

In the summer of 1967, she and two friends hitchhiked across country to San Francisco. They went to the Haight-Ashbury switchboard to get connected with temporary housing. She remembers, “the Rolodex card they pulled for us was Vincent O'Connor of the Catholic Peace Fellowship. And I got to go with Vincent O’Conner down to the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence in Carmel Valley, run by Ira Sandperl, Joan Baez, Roy Kepler. And they organized the first ever nonviolent civil disobedience action in opposition to that war in Vietnam. Jail, no bail. What if we had walked in there one hour earlier, or one hour later? We would not be having this conversation. Unless you believe in predestination. I mean, I think about those moments, like ‘what if?’ and how incredible. But I just feel honored and humbled, you know?”

This was at the height of the US war on Vietnam, and hundreds of thousands of young men were being drafted. Mandy was barely out of her teens the first time she was arrested, along with Joan Baez and others doing nonviolent civil disobedience at the Oakland Induction Center. During her ten days in jail, Mandy was introduced to the War Resisters League (WRL). She began volunteering with them, and then was hired onto the staff. “That was my first job. I got $80 a month, that was it. But I got free dental and I got free health care, because they had doctors that were with the War Resisters League that provided that as an in-kind service. I slept on the couch in the office, and I answered that phone 24-7. That was home.”

Mandy went to Washington DC in 1968 to join the Resurrection City encampment, inspired by Dr. King, as part of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s multiracial Poor People’s Campaign. While there, she was arrested for the second time doing nonviolent civil disobedience.

She describes the Western Region War Resisters League staff of the 1970s as comprised of “WWII conscientious objectors and Vietnam War draft resisters, openly gay men, fierce women, and myself—an out Black lesbian.” In a 2018 statement she wrote, “most WRL offices in that time were run primarily by straight men. But we brought feminism—gender and sexuality justice—into WRL’s antiwar space, making the then-radical connection between feminism and antiwar efforts, asserting that the same toxic masculinity that hurts women and femmes at home drops bombs and destroys communities across the world.”

Mandy is one of six lesbians—by intention, three Black and three white—who co-founded the organization Southerners on New Ground (SONG). Over its more than 30-year history, SONG has “ignited the kindred” through transformative models of organizing that connect race, class, culture, gender, and sexual orientation. They cultivate the grassroots leadership of thousands of Southern rural LGBTQ+ people from all walks of life in a movement for dignity and justice. One of SONG’s greatest strengths is its commitment to intersectionality and whole person organizing, where all of a person’s identities are honored and no one is forced to leave parts of themselves behind.

SONG was born out of the 1993 Creating Change Conference of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (now the National LGBTQ Task Force). Usually convened in WDC, they lost their venue at the last minute and reached out to Mandy to ask about hosting it in Durham, NC, where she was living. Knowing the strong base of queer activists in the area, she readily agreed to help organize it and, for the first time, the conference was held in the South.

Several of the women who would become the founders of SONG put together a workshop for the conference about living and organizing in the South. Mandy recalls, “So, I think, because we did that workshop at Creating Change we said, ‘well, wait a minute. If we can do a workshop around Black and white, and how we can talk about all these other intersecting issues, maybe we should start an organization.’ And that really became the foundation of Southerners on New Ground.

“If I'm not mistaken, all of us were already involved in other things. Mab Segrest was doing NCARRV, North Carolinians Against Racist and Religious Violence. Joan Garner was actually an Atlanta County Commissioner. Pat Hussein was down in Atlanta doing Olympics out of Cobb, to counter the anti-gay discrimination in the Olympic games. Suzanne Pharr founded the Arkansas Women’s Project. Pam McMichael was in Louisville doing work around Jobs with Justice. And I was here with the War Resisters League.”

Several generations later, the organization is still going strong.

Given her long years in movement work, I invite Mandy to talk about what she has learned along the way that she wishes she had known starting out, or that might be helpful to others. “Okay, I think, a couple of things. One of them is humility. To do more listening and critical thinking. And maybe asking a question with a question mark at the end, versus making a statement. I’ll admit 'I don't know,' in a good way, right? ‘I don’t know, but let’s just figure this thing out.’ I've always been one of the most curious people—what about that, and what about this, and whatever. Just having interest and being intrigued, and reaching out and trying to find some way to be the bridge, the bridge builders. You know, as a personality, I could talk to a total stranger. I'm just like that, an outgoing kind of person.

“I was thinking of the cycles of our change in American society. And also, the principles. What I love about Quakers, it's like, it's not about me. ‘The power of one.’ That's the thing, Liza. That every one of us has all kinds of wonderful opportunities and possibilities. There's no guarantee. None. And if there’s a way that you can be, I would say, proactive. Look around at your situation. You know that wonderful quote: ‘don't mourn, organize.’ If there's a need, fill it. In fact, I think maybe for the next year or two, I might be interested in going back into foster homes and group homes, because that's where I came from.”

She continues, “One of the other things I love with the Quaker tradition is that when people were going to do civil disobedience, everyone had the choice. If you want to sit in and go to jail, fine. If not, fine.” She describes an array of ways people could participate without risking arrest—as legal observers, or attending to the support needs of folks on the line. “You know, it was much more of a collective sense of a WE. It was like, the more the better. And the power of one is wherever I move around. If I look at, like, who else, whose lives am I touching and who touches mine. I love that.”

Mandy talks a lot about “the power of one,” attributing it to the Quakers who were so instrumental in her activism. What she means by it is not a heroic one, not the power of a single charismatic leader out in front, but the power of the small ways each of us can have impact greater than we will ever realize. She offers the example of the young white AFSC speaker who came to her high school, not knowing that his routine presentation would catalyze a lifetime of committed activism in one of the students, and all the lives she would go on to touch. Or the woman who casually invited her to a War Resisters League potluck when she was in jail for protesting the draft, and how that set the course for her decades of involvement with the organization.

“When you see that,” Mandy affirms, “you think, not if, but when. And what role do I get to play in that? And then invite as many people as you can into it. Anyone can do it. Anybody. Just pass it on. The thing I love the most is not just because I can do it, but then who else can be engaged to say, you can do that too? And then people literally intentionally getting together, making the change and thinking outside the box.”

“We're in an interesting generational time. So, I think I'm in a moment of reflection. I want to be quiet. I’m slowing down, but I still want to be a part of what can happen to make people's lives change. I certainly want to be organized around this 2026 election coming up.

“And now that we're all getting older, but we're still here—I'm still here. You're still here. Other people are. And other people left their legacies, you know. I'm thinking of friends that I've lost. There was such a dedication to their purpose and their core part of that. So I wake up every morning and say what's the one thing I'm going to do today? And then let's go make that happen.”

As we wrap up, I ask Mandy what keeps her going; what inspires her to do the work? “Possibilities,” she replies, without hesitation. “And to see it, to see the change. The possibilities are there. And then what role do we play, each in our own way? And how do we be inclusive, and also get joy, and involve other people who are just starting out. Each one, reach one. Each one, pass it on.”

Please join the conversation by adding your comments below, or click the heart if you enjoyed this article!

To Learn more about Mandy’s work visit:

“Meet Mandy Carter, the legendary ‘Scientist of Activism’ who fought for Black and LGBTQ+ rights in the American South.” https://www.reckon.news/lgbtq/2024/03/meet-mandy-carter-the-legendary-scientist-of-activism-who-fought-for-black-and-lgbtq-rights-in-the-american-south.html

“Black History Month: Mandy Carter,” Curve Magazine (2020): https://www.curvemag.com/blog/activism/black-history-month-mandy-carter/

“Mandy Carter: Scientist of Activism” special exhibit at Duke Library: https://exhibits.library.duke.edu/exhibits/show/mandycarter/intro

Book Mandy co-edited with Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez and Matt Meyer, We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and Militarism in 21st Century America (2012).

I LOVE "asking a question with a question mark at the end, versus making a statement." This kind of humility and curiosity is the sign of a true, wise elder!

Excellent interview and important introduction of Mandy. Her activism is inspiring and her life is Black History made real!!!