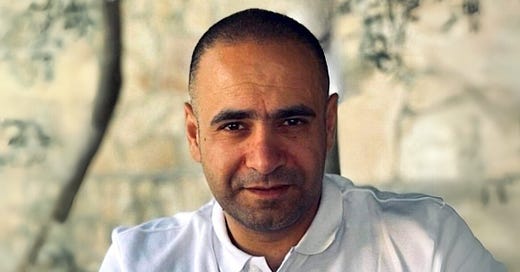

Rami Khader: Resistance, Resilience & Love

Healing Conversations from the Front Lines of Activism

Dear Friends, I greet you with tenderness. There’s a way that all of us are on the front lines in these times of upheaval, but some of us are more literally on the front lines than others. This month’s conversation with Rami Khader, who lives and works in the occupied West Bank, gives evidence to the power of healing even in the midst of ongoing violence and devastation.

Rami Khader is a humanitarian, social worker, activist, and community mobilizer from Bethlehem, Palestine. He is the founder of several organizations that combine arts and culture in service to community healing. Central to this commitment is the organization Anar, which in Arabic means “to light up” or “to bring back the light.” Through advocacy and community-based psychosocial services, they aim to break the cycle of oppression and intergenerational trauma, fostering collective resilience and hope.

Rami writes, “Embracing liberation as a way of life involves more than just seeking to be free; it's also about embarking on a journey of self-discovery and self-healing, where one's inherent value is acknowledged and validated.” Anar recognizes “the systemic and structural factors that contribute to trauma and oppression, and aims to address them through a collective and empowering process of healing and transformation. By doing so, it not only helps individuals to heal from their personal traumas, but also cultivates a sense of agency, solidarity, and resilience within the community as a whole.”

Rami and I were introduced by a mutual friend who had met him while doing accompaniment work in the occupied West Bank. This interview was our first conversation, held across a 10-hour time difference and more than 7000 miles.

As we figure out the tech challenges and settle into our zoom call, I begin by asking Rami what comes up for him when he hears the title of this blog, Healing Conversations from the Front Lines of Activism. “It really brings up everything,” he replies. “It somehow speaks about two important things in the Palestinian struggle for freedom. One is healing that is much needed at the moment. Not only because of the trauma that is currently affecting the population—children, caregivers, communities—but also the intergenerational trauma that has played a vital role in shaping our identities as oppressed under the violence of Israeli military and settler occupation.

“The second component,” he continues, “is the advocacy part, the need to raise our voices against the brutal machinery and the occupation that does not steal only people's properties and lives, but steals their souls and minds as well. It is so important that we think of both together.”

Ultimately, these are two interdependent aspects of one thing. As Rami points out, “The justice is not only an action, it's a healing process. Without justice, it is so hard to do healing. The cycle of oppression itself is what is traumatizing. So, breaking the cycle of injustice is an act of healing.”

Not everybody that I interview for these conversations identifies with the term “activist,” in part because it is fraught with so many different nuances and meanings. I’d noticed in my research that Rami actually does refer to himself as an activist, so I’m curious how he defines it.

He is thoughtful, “In the first sense of it, it's a personal journey inside out. It starts in the individual by feeling what is going on in this world, and why do we really need to break the chain of oppression around us, starting from us as individuals and growing to the wider issue, to the wider world. It's really an individual healing process and self-conscious process toward wider action—which is exposing yourself, your life, all you have—for a noble idea, against oppression, against the materialistic world that we live in, against anything that causes harm to others.

“I grew up under military occupation my whole life,” Rami explains. “I knew it as a child growing to understand that the sky is not our limit, rather that walls and checkpoints and military occupation is our limit. Here, I'm not just referring to the physical limit, but also what is possible for us to dream about, as well. So advocacy to me, being an advocate to the stories I have witnessed, and also the stories of others, is an act of resistance, is an act of refusal to what we see and experience on a daily basis.

“But what really makes me very keen is seeing a 12-year-old child being detained in Israeli prisons. Seeing children while they are going to school, they experience tear gas. Seeing the children in Palestine experience not only death, oppression, being held at checkpoints, but seeing them talk like adults from what they have endured. It seems like it is the un-childing of children that really affects me the most.”

It was witnessing the impacts of this ongoing trauma on children that led Rami to found Anar. As he describes their programs, I am profoundly moved by the love that animates them, and impressed by their thoroughness in addressing the mental health needs of children, parents, and communities.

“Just recently, we have done a drama session for children. It was children who were living in one of the local refugee camps here in Bethlehem. The social worker came to us after the first session. She said that none of the children were able to move. All of them were very rigid. They didn't want to express themselves. And what strikes her is that none of them was able to really imagine. When she asked them to imagine this or imagine that, none of them really wanted to go to that place.

“Usually, we do eight sessions. It took her three sessions in order to move the children. But once they moved, and believed that this is possible again, they didn't want to stop. They loved it! It brought back childhood to them. And when the last session ended, that was like a big cry for ‘We need more! We need you to be with us again!’ This is what really drives us here to keep going. The kind of work we do is a tough one. But what gives us that glimpse of hope is those images of children once they start to be children again.

“This is why I really like the arts, and we use the arts for our healing practices, because the brutal experiences people go through are extremely difficult. Arts can really play an important part, not only in their healing process, but in their ability to speak their story.”

I have never been moved to tears in an interview before, but I cannot even begin to imagine the difficulty of doing the work that Rami and his colleagues do on a daily basis, and in the context of ongoing occupation and violence. I confess this to Rami, and then ask how, in the face of such difficulty—where he and his colleagues are also being traumatized as they do the work—how do they sustain themselves in the face of that?

“I'm very aware that secondary trauma is a difficult form of trauma as well. As much as we really want to support all the community, supporting ourselves as well is the starting point to that healing process—because if we don't do that, we will end up traumatized ourselves. For that, what we have done is that in our organization, we have a program that is to heal the healers. We provide emotional supervision to counselors, to staff members, who experience what they experience on a daily basis. We talk about it. We're open about our vulnerabilities as well. We have created a culture in our organization that is very understanding to people's feelings and difficulties and emotions.”

He continues, “As much as we do, there will be spaces, places, where we will be weak. Trust me, every time I sit with a child who has been in prison and he or she tells me about what they have done, I cry like a baby. As much as I tried to really not do it in front of the child, it fails me every time. We just have to be aware and try as much as possible to heal ourselves as well, and to provide ourselves with time, enough sufficient time, to process what we experience. But still, vulnerability is very high in what we do.”

“Are there specific practices that you yourself use to help sustain you, and to replenish and renew your own spirit in the face of this?” I ask.

“For me,” Rami says, “every time I feel really down, I feel that I'm unable to process what I have heard and all of that, I go and talk to children. Especially children who we worked with, because then they bring me back to the purpose of the work. Why we do what we do.

“As a parent, I have a very clear line that is drawn between what is work and what is family. What time is for work, and what time is for my family and my children and my wife, to be with them as a family and not do work. Because that is important as well. But really, finding support systems around you, whether it is your family, whether it is your friends, whether it is other professionals—that component of community is important in our culture, but also in our practice as well.

“When we are enthusiastic about the cause, or about people's experience of oppression, and we want to really change the world, we sometimes neglect ourselves or neglect our families. That balance between yourself, your family, and the purpose of your life, is extremely important. Neglecting one over the other will harm you as an individual.”

The reminders he offers about the necessity of support and balance, about staying connected to the purpose that inspires, are wise counsel for so many of us in these times, whatever we may be navigating.

The methodology of Rami’s work is, in itself, life-giving. Even before founding Anar, through his other organizations and teaching, Rami has engaged the arts as a practice for therapeutic self-expression, empowerment, and healing within Palestinian communities. With the well-being of children at the center, Anar has created an ecosystem of programs to address the needs of different populations within the community in a sustainable way—parents and caregivers, young adults, elders.

He recalls, “When we initiated Anar, we thought, the need is huge and our resources are few—what shall we do? From discussions and research, we thought that in order to heal the generational trauma, the historical trauma, the current trauma, and the oppression that people experience at the moment, we have to strengthen the resilience of our communities. We have to bring communities to a place where they start to adapt healing practices within their local cultural practices. This way communities can heal by themselves, and make it more a collective healing process rather than only an individual healing process.

“One of the ways we do that is through a program called ‘self-help hubs.’ Those hubs are a group of young people in their 20s and 30s—professionals, jobless youth, youths excited about the world, activists. We train them on psychological first aid, how to initiate psychosocial sessions, how to do psychoeducation, how to hold healing circles for children and caregivers. And we provide them with the supervision needed from A-point until Z-point.

“We only have eleven staff members in the West Bank, but because we have trained hundreds of youth around the country, around the West Bank, our practices have been reaching out to every single community through the young people we have trained and coached and supported.”

With this methodology, these young adults not only receive coaching and learn valuable skills, they are given jobs by Anar to serve their communities. This provides them with a much-needed sense of purpose, agency, and dignity. Rami sees this investment as key to the sustainability of the work, and as an investment in the future of Palestinians.

“One thing I really have to highlight here,” he says, “is that I have been blessed with the people around me who make all this possible. Starting from our board, but also my colleagues on the ground, who really believe in what we do. Believe to their core. It's not a job. To us, this is not a job. You would see us having fun doing things, because it really comes out of our heart and our ability to see the need as well. I'm blessed with these individuals around me because they made it really possible.”

A recent addition to the team is a sister organization to Anar based in the US, Healing to Hope. Their aim is to foster healing in Palestine by elevating the work of Anar, and helping to raise both awareness and funds.

“We have been waiting for that moment of freedom and are still looking for it, and acting for it. But it hasn't come yet. Sometimes, honestly, it feels like this is going forever. The fact that this occupation is never-ending, is traumatizing. And I struggle with it. I'm not sure how, but the next morning, I wake up with an opposite feeling like, ‘This is a new day! We try again!’” Rami smiles, “And I have been feeling that for the last 30 years, every day.”

As we bring our conversation to a close, I ask Rami about the vision he is working toward. “Well, as someone who has invested his life in healing, and healing practices, and I mentioned to you that a big part of healing is solving the root cause of the oppression, which is people's freedom. This is my vision into the future. I will keep resourcing every single minute of my life in the healing practices until we see freedom possible. And it will be possible one day.”

Please join the conversation by adding your comments below, or click the heart if you enjoyed this article!

To Learn more about Rami’s work visit:

Anar’s website: https://anar.ps

Healing to Hope: https://www.healingtohope.org

Anar’s Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/anarbethlehem

Rami’s LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rami-khader-37195a9a

“An Interview with Rami Khader, Director of the Diyar Dance Theater” (2017): https://dctheaterarts.org/2017/07/15/bethlehem-philadelphia-interview-rami-khader-director-diyar-dance-theatre

“Embracing liberation as a way of life involves more than just seeking to be free; it's also about embarking on a journey of self-discovery and self-healing, where one's inherent value is acknowledged and validated.” This is so powerful. Moved to tears.

Thank you Liza and Rami for this powerful conversation, all the wisdom and insights offered, and for taking the time to share it with all of us. Much respect and gratitude.